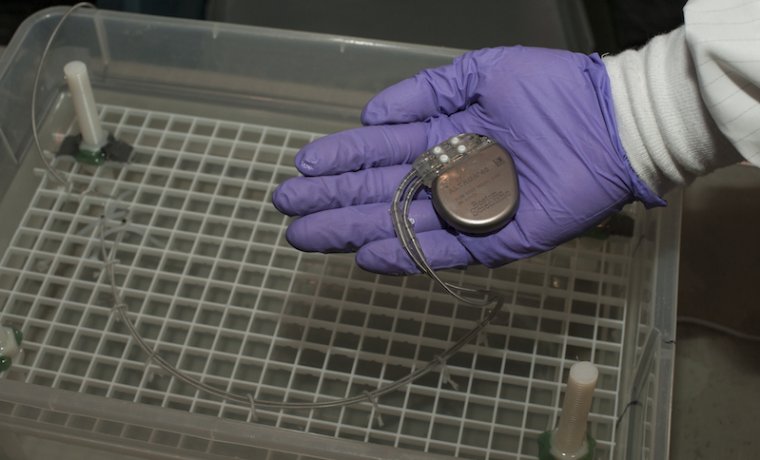

Pacemakers are devices that are implanted in the chest or abdomen to control life-threatening heartbeat abnormalities. Once they're in place, doctors use radio signals to adjust the pacemakers so that additional major surgeries aren't required. A study recently found that pacemakers from the four major manufacturers contain security weaknesses that make it possible for the devices to be stopped or adjusted in ways that could have dire effects on patients.

Chief among the concerns: radio frequency-enabled pacemaker programmers don't authenticate themselves to the implanted cardiac devices, making it possible for someone to remotely tamper with them.

"Any pacemaker programmer can reprogram any pacemaker from the same manufacturer," researchers from medical device security consultancy WhiteScope wrote in a summary of their findings. "This shows one of the areas where patient care influenced cybersecurity posture."

WhiteScope researchers went on to say that the risk is compounded by the availability of pacemakers, programmers, and device monitors to anyone on eBay, despite manufacturers' claims that general availability of the devices is "controlled." WhiteScope researchers said they were able to discover key weaknesses after purchasing such equipment for prices ranging from $15 to $3,000.

After analyzing the devices, the researchers discovered more than 8,000 known vulnerabilities in four different programmers from four different manufacturers. In two cases, they also found patient data stored unencrypted in the devices they bought. The patient data came from "a well-known hospital on the East Coast," the researchers said, without naming the facility. In a report, researchers Billy Rios and Jonathan Butts wrote:

This paper provided findings from analysis performed on the implantable cardiac device ecosystem architecture and implementation interdependencies. WhiteScope identified potential areas of concern with the underlying architecture and obtained vendor devices to evaluate system implementations. The findings reveal that the inherent architecture and implementation interdependencies are susceptible to security risks that have the potential to impact the overall confidentiality, integrity and availability of the ecosystem. The findings are relatively consistent across the different vendors, highlighting the need for all vendors to perform an in-depth and holistic evaluation of implemented security controls. Given the commonality of the findings across different vendors, identification of implementation vulnerabilities as to any one vendor may expose those same vulnerabilities in other vendors and should be considered carefully before public disclosure.

By ensuring appropriate security controls are implemented, vendors can help protect against potential system compromises that may have implications to patient care.

It's not the first time security experts have issued such warnings. In 2013, the Industrial Control Systems Cyber Emergency Response Team and the US Food and Drug Administration issued separate advisories warning that a wide array of medical devices—including drug infusion pumps, ventilators, patient monitors, and surgical and anesthesia devices—contained hard-coded passwords. Attackers who know the default passwords of the devices can exploit these backdoors and change critical settings or replace the authorized firmware altogether. The advisories came in response to findings Rios and colleagues provided privately to the agencies.

There are no reports of malicious medical device hacks that have been carried out, but in 2013 former Vice President Dick Cheney said he considered the threat credible enough that he altered the defibrillator implanted near his heart to prevent attacks. Unlike many hack attacks, medical device tampering would usually require extremely close proximity to the target, making wide-scale attacks infeasible. They also wouldn't provide the kind of easy profits that motivate more traditional hacking crimes. Still, there's something unsettling about life-critical medical devices lacking the kinds of security precautions that come standard in many smartphones.

reader comments

92