Tetris is good for easing the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), scientists have found. Yes, you read that correctly: the infuriating, mind-swallowing piece-twiddling row-building game actually has a medical value.

The research, which was conducted at the department of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, suggests using Tetris as a "cognitive vaccine" against flashbacks from traumatic events. It's published on the open-source science research Public Library of Science (PLoS) website.

Here's how they set out their recommendations:

The rationale for a 'cognitive vaccine' approach is as follows: Trauma flashbacks are sensory-perceptual, visuospatial mental images. Visuospatial cognitive tasks selectively compete for resources required to generate mental images. Thus, a visuospatial computer game (e.g. "Tetris") will interfere with flashbacks. Visuospatial tasks post-trauma, performed within the time window for memory consolidation, will reduce subsequent flashbacks. We predicted that playing "Tetris" half an hour after viewing trauma would reduce flashback frequency over 1-week.

In other words, if you're looking at falling squares, lines, hoooks and whatever those twiddly ones that are two overlapping lines of two are called, then you don't have time to visualise your previous bad experiences.

I'm glad I wasn't asked to take part:

Forty participants watched a 12-min film of traumatic scenes of injury and death (n = 20 per group). Film viewing was followed by a 30-min interval before simple random assignment to one of two experimental conditions. There were no baseline differences between the two groups in terms of age, depressive symptoms or trait anxiety or gender. Mood was equivalent between the groups prior to watching the film, and as predicted, both groups experienced comparable mood deterioration following the film (emphasis added).

(Tell me about it. Someone at work was looking for gruesome scenes from ER involving helicopters and instead found a real-life one. I'm recommending Tetris to him.)

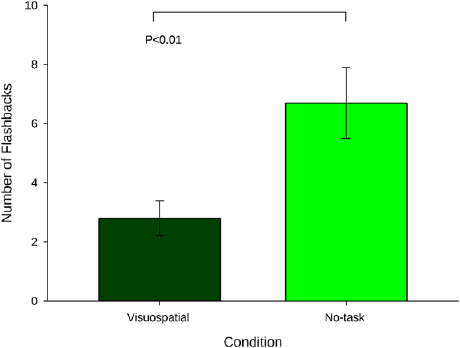

Afterwards, one group just sat quietly, and another played Tetris, for ten minutes. They then kept a diary about flashbacks they'd had; this showed that the group which had played Tetris had significantly fewer (with a probability that it was chance less than 1%).

It's a remarkable finding; though looking at the long list of references, the idea of visual "distraction" as a method of desensitising people from visual memories has been around since at least early this decade.

But who'd have thought we'd find a potentially workable cure in a game that for a while 20 years ago seemed like a Russian plot to turn all our population into obsessive cursor-button pokers? (Wait, did it work?)

So maybe that's going to be the new treatment for returning soldiers from the front: Nintendo Gameboys loaded with Tetris. Then, all we'll have to worry about will be curing their Tetris addiction.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion